In his speech last Friday, the mayor of London stressed that his green belt review was a radical policy change. Š½Č½ė░╩ė probed him on what kind of land could be targeted and combed through his consultation documents for clues to where homes could be built.

When politicians break their promises, they generally try to downplay the matter. But delivering a set-piece speech atop an exposed construction platform in Kidbrooke Village, under a beating sun and several storeys above the ground, Sadiq Khan clearly wanted this U-turn to be made in the bright light of day.

For years, the mayor of London has promised to protect the capitalŌĆÖs green belt. Then, in his big speech last Friday, he announced that was set to change.

Launching a consultation which will lead to a draft for the next London Plan, Khan said that his office was going to ŌĆ£actively exploreŌĆØ development on select areas of the green belt.

Speaking to journalists after his speech, the mayor was upfront about his decisions. ŌĆ£I make it a virtue, IŌĆÖve changed my mind,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£If weŌĆÖre going to meet the needs of our city, we have got to be exploring those parts of the green belt.ŌĆØ

ThatŌĆÖs all well and good rhetorically, but to any neutral observer it is hard to avoid the fact that this is a decision that he has been forced to take. For all the hostilities between Khan and the Conservative party, the ironic truth is that the ToriesŌĆÖ laid-back approach to housing targets, adopted to satisfy the partyŌĆÖs rural backbenchers, have helped London to get away with consistently undershooting its assessed housing need.

When Labour came into government with a revamped standard method that abandoned the urban uplift, LondonŌĆÖs assessed need dropped from around 100,000 homes a year to around 88,000. But the change to targets came with a message that this government was really serious about making sure they were delivered.

If plan-making authorities cannot demonstrate how they will meet their targets using brownfield, then, under the new rules, they are required to look at low-grade green belt land ŌĆō labelled grey belt by central government.

While the last London Plan, adopted in 2021, had a target of around 52,000 homes, the most recent annual delivery figures stood at just 35,000. Speaking to Š½Č½ė░╩ė on Friday, the mayor himself acknowledged that there was no way of making up the shortfall without a radical change.

ŌĆ£Even if we max out all the brownfield sites over the next 10 years at the same record-breaking levels as the last nine years, weŌĆÖre still quite a way short,ŌĆØ he said.

What is the London Plan?

The London Plan is the strategic spatial plan for Greater London, setting out strategy and requirements for homes, transport and other infrastructure. It sets out how the capital should develop over the next 20-25 years.

When London boroughs write their own plans, they have to be in ŌĆ£general conformityŌĆØ with the London Plan.

The current plan was published in March 2021. The draft new plan will be published in 2026 for consultation. The new plan will then run from its adoption in 2027 until 2050, with regular updates.

On Friday, the mayor published an initial consultation paper (Towards a New London Plan) featuring proposals that might be included in that draft. It gave a strong indication of his thinking and priorities.

The plan also sets housing targets for each borough to achieve, which it bases on where homes might reasonably be built, rather than where local need arises. In other words, London is treated as one big housing market, despite having more than 30 planning authorities.

Explaining his plans, Khan emphasised the radical nature of his proposed green belt review, which he said would go ŌĆ£over and aboveŌĆØ the governmentŌĆÖs grey belt definition, while insisting that ŌĆ£nobodyŌĆÖs talking about touching their gorgeous parksŌĆØ. So, what kind of land are we actually talking about here?

The consultation papers published alongside KhanŌĆÖs speech provide a little clarity. He proposes that the London Plan be redrafted to distinguish between metropolitan open land (or MOL, publicly accessible parks and fields) and green belt, in order to protect the former from the planned reviews. However, another line from the document sets out a notable exception to this rule, indicating one example of the kind of areas that could be brought into development.

ŌĆ£Given the challenging housing target, there may be some very specific circumstances where certain MOL, such as golf courses, could be considered for release for housing,ŌĆØ the document says. According to a report by BusinessLDN (albeit dating back to 2015), 7.1% of LondonŌĆÖs green belt is made up of golf courses.

In his comments to journalists, Khan stressed over and over again three features of the kind of land he wanted to look at: ŌĆ£Poor quality, badly maintained, not accessible to Londoners.ŌĆØ

The mayor claimed that just 13% of LondonŌĆÖs green belt was made up of parks or areas accessible to Londoners and that a lot of what was left was not ŌĆ£green and pleasantŌĆØ or ŌĆ£rich in wildlifeŌĆØ. BusinessLDNŌĆÖs 2015 report said that combining public access land with land subject to environmental designations would get you to 22% of the green belt.

So, beyond the disused green belt petrol stations and garages that are included in the grey belt definition, it seems like the best guess for the kind of land KhanŌĆÖs review is set to target will be golf courses and areas of farmland with poor biodiversity credentials.

The mayor was also clear that there will be a range of conditions attached to development on green belt land. ŌĆ£We are not going to allow these executive homes, low-density luxury homes, to be built on this green belt,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆØWhat weŌĆÖre going to do is attach conditions. TheyŌĆÖve got to be good quality, well-designed, [and] maximise affordabilityŌĆØ.

So, where is all this land anyway? Khan warned journalists on Friday against ŌĆ£prejudging the consultationŌĆØ, but information included in the documents, alongside publicly available data, does provide some clues.

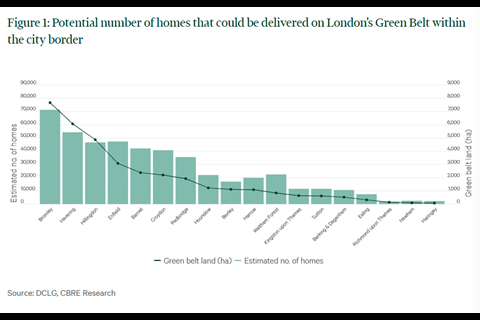

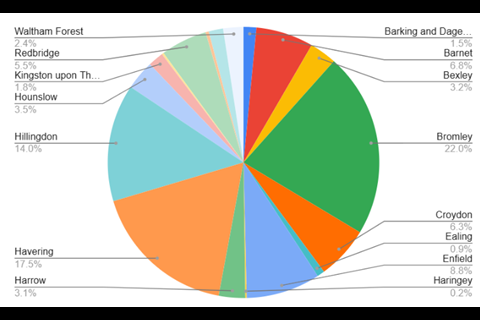

In pure numerical terms, more than 50% of the green belt falls within three boroughs: Bromley (22%), Hillingdon (14%) and Havering (17.5%). Research by CBRE has estimated that almost 70,000 homes could be delivered on the green belt in Bromley alone, with similar amounts in the other two areas.

But this does not necesarily mean that these areas are where development will predominantly fall. For one thing, it is unclear how similar the property consultantŌĆÖs methodology for identifying suitable sites is to the one that will end up being developed through the green belt review.

As is clear even from CBREŌĆÖs chart, some outer London boroughs would give you more bang for your buck ŌĆō Enfield, for example, is shown to have slightly higher potential for housing development than Hillingdon, despite the former having more green belt land.

Quite plausibly, there could be a decent amount of green belt released in dribs and drabs, through small packages of land near existing stations in places like Redbridge. But the mayorŌĆÖs consultation indicates that his office sees the potential for chunkier developments in the green belt ŌĆō even talking about potential new towns.

ŌĆ£Opportunities for large-scale development (10,000-plus homes in each location) in LondonŌĆÖs green belt are being considered in areas with good public transport access (or where this could feasibly be delivered),ŌĆØ it says. ŌĆ£There is also significant potential with the governmentŌĆÖs New Towns Taskforce, which we will be engaging with.ŌĆØ

One thing that the mayor was clear about across his speech, comments to journalists and in the consultation documents, was the link between green belt release and public transport connections (both existing and proposed). ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre going to make sure any land release has got good transport connections,ŌĆØ he told Š½Č½ė░╩ė.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no point releasing green belt if youŌĆÖve got to drive to and back from it.ŌĆØ

The consultation documents explain that the mayorŌĆÖs office is ŌĆ£starting to explore at a strategic level potential new public transport that could unlock further housing capacityŌĆØ, including ŌĆ£new stations, increasing rail frequencies, and possibly extending existing linesŌĆØ. According to BusinessLDNŌĆÖs 2015 report, around 60% of LondonŌĆÖs green belt is within 2km of an existing rail or Tube station, falling to 42% once environmentally protected land, parks and public access lands are excluded.

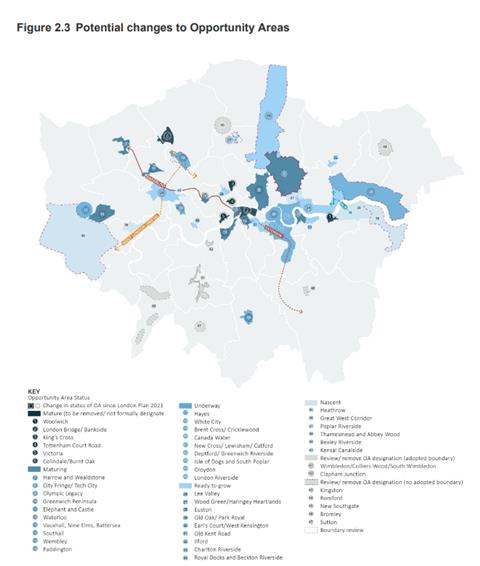

The routes of recent and planned transport infrastructure upgrades, along with the ŌĆ£opportunity areasŌĆØ identified in the consultation document for the next London Plan, together give an indication of some potential areas for significant green belt development. Almost 100,000 homes have been completed in opportunity areas during the current London Plan monitoring period.

Part of HaveringŌĆÖs green belt falls within the ŌĆ£London RiversideŌĆØ opportunity area, a huge stretch of land identified for redevelopment which includes the Barking Riverside development already under construction. Notably, Havering has recently benefited from the addition of three stations on the Elizabeth line: Romford, Harold Wood and Gidea Park.

Across the river is the Bexley Riverside Opportunity Area, which includes part of BexleyŌĆÖs green belt. The previous London Plan identified potential for 6,000 new homes in this area. It is one part of London where housing delivery could benefit if the mayor is successful in turning existing National Rail lines into a metro.

ŌĆ£Many National Rail lines serving suburban areas could have higher ŌĆśmetroŌĆÖ-like frequencies with relatively modest infrastructure improvements,ŌĆØ according to the consultation document. ŌĆ£This could enable more mid-rise and small-site development across a much wider area.ŌĆØ

Khan has previously expressed an interest in ŌĆ£metro-isingŌĆØ the Southeastern line that runs through the Bexley Riverside area. More speculatively, there have been investigations by the C2E Partnership into the possibility of extending the Elizabeth line from its terminus at Abbey Wood into Kent, passing through Belvedere and Slade Green in Bexley Riverside.

Up north, there is the huge Lee Valley Opportunity Area, which stretches up to the chunk of green belt at the very top of Enfield. This area has good existing transport links via the London OvergroundŌĆÖs Weaver Line, while the most recent proposed route for Crossrail 2 also runs through the area. That being said, much of the green belt in this area is environmentally protected wetlands.

At its southernmost tip, the London Borough of Kingston also has some green belt situated near an identified opportunity and along the most recently proposed route for Crossrail 2. However, under the new London Plan consultation, KingstonŌĆÖs status as an opportunity area is set to be reviewed ŌĆō and could be removed.

The consultation document said de-designation may take place where ŌĆØtransport infrastructure schemes are now less certain or will only be delivered beyond the next decadeŌĆØ, giving the example of Crossrail 2.

Number of homes that could be unlocked by transport upgrades

Crossrail 2: 200,000 homes

Docklands Light Railway extension: 30,000 homes

Bakerloo line extension: 20,000 homes

Devolution of Southeastern: 10,000-20,000 homes

West London Orbital: 7,000 homes

Devolution of Great Northern: 4,000 homes

HS2 to Euston: 2,500 homes

Figures sourced from the London Growth Plan, published in February this year.

Areas of green belt around Heathrow, in both Hillingdon and Richmond upon Thames, could also be targeted. Hillingdon has the third-largest chunk of green belt in London, while the Heathrow opportunity area includes green belt near Hampton in Richmond upon Thames.

The Elizabeth line provided a new link to the area, and Hampton was included in the most recent Crossrail 2 route.

But all of this is just speculation. The green belt review may well find that certain promising areas in fact face insurmountable obstacles to development, while less obvious targets turn out to be a perfect fit.

One frustration is that four Tory-run councils, including some of those with the biggest chunks of green belt, have already refused to join KhanŌĆÖs review. Bexley, Bromley, Croydon and Hillingdon will all still have to conduct reviews of their green belts, but independently, potentially frustrating attempts to take a more strategic approach.

What is more, as is abundantly clear from the above, the suitability of many areas for large-scale development will depend almost entirely on which transport schemes the government agrees to fund (assuming it can afford to back any).

And it is not just green belt development that is dependent on infrastructure investment. There are a string of opportunity areas running along the route of the Bakerloo line (Harrow, Wembley, Old Oak, Paddington, Euston, Waterloo all have opportunity areas) and its extension (Elephant and Castle, New Cross, Lewisham, Catford, Depford and Greenwich Riverside).

Meanwhile in east London, Thamesmead has been identified as having the potential for a large-scale development ŌĆō but progress is dependent on funding for the DLR extension.

The consultation document acknowledges that it is very much at the mercy of the Treasury on this front, noting that ŌĆ£concerted action is needed beyond the London Plan to unlock tens of thousands of homes from large-scale rail projectsŌĆØ, including ŌĆ£government commitments and funding or financing to support their deliveryŌĆØ.

Reading between the lines, you could assume that the mayorŌĆÖs repeated mention of improved transport links as the basis for increased housing delivery indicates that he is expecting a major package of investment in the upcoming spending review. Notably, he told journalists that his decision to change his position on the green belt after all these years came because he had increased confidence that he would receive the investments necessary to make it work.

ŌĆ£I have got a government that is supporting our vision of meeting the needs of our city, but also, really importantly, supporting us with transport infrastructure investment.ŌĆØ Khan said. ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖve seen over the last nine years, an anti-London government not investing in TfL, let alone new transport infrastructure.ŌĆØ

On the other hand, last Friday could have been the mayorŌĆÖs big pitch to central government for an injection of cash. If he has any clue about whether the chancellor Rachel Reeves is minded to splash out, he did not give it away down in Kidbrooke Village.

ŌĆ£Unless you know something I donŌĆÖt know,ŌĆØ he told Š½Č½ė░╩ė, when asked whether he had been given assurances on schemes like the Bakerloo extension. ŌĆ£I see them all the time. They give you no commitments at all.ŌĆØ

No comments yet